Can differences in self-confidence between women and men be observed from what they say?

Introduction

Motivation

It shouldn’t be news to anyone that gender inequalities are rife in modern society. For many centuries, women and other non-male genders have often been oppressed in western cultures. Systematically being denied political, economic and intellectual power, women have been regularly stereotyped as caring and nurturing by nature, to be necessarily relegated to housework and childcare, whilst men had ease of access to higher education and financial independence. Although Women's Rights Movements have greatly improved women's conditions, inequalities subsist today. Positions of power, be it in politics or private companies, are still mostly occupied by men, whereas women find it harder to access such opportunities. A rather striking example can be seen in the huge difference in the number of women and men pursuing higher education, such as at EFPL. Other examples are still very common and present in everyday life but such inequalities can also be transmitted via implicit bias, where women are seen as less competent than their male counterparts.

As differential treatment and stereotypes lead to differences in self-assessment and behavior, it is no surprise that researchers have found a worrying trend that women tend to underestimate their abilities more than men and frequently experience "Imposter Syndrome", wherein they feel as though they are not qualified for their position and fear they will be discovered as such.

We are interested in the difference in self-confidence between men and women. Have oppression and stereotypes lead to women feeling less confident? If so, is this asymmetry noticeable in the way people express themselves? This analysis can be taken further and it would be interesting to see if professions could influence self-confidence. For example, could being a public figure, as politicians are, skew one’s self-confidence and do genders still play a role even in such professions?

Method

For this short study, we decided to use the Quotebank dataset from the year 2020, which consists of quotes taken from English language newspaper articles and web domains, with the speaker attributed to the quote by the Quobert framework. Our self-confidence metric is based on "Verbal Expressions of Confidence and Doubt", a psychology paper published in 2009, which rated the percieved self-confidence of speakers through their expression. The personal information of quoted persons such as their gender, birth year and occupation was retrieved from Wikidata.

Some statistics on the speakers:

Let's start by looking at the gender distribution of speakers:

We can see above that a vast majority of the speakers are females and males (these categories include cis-gender and unspecified females and males), even though there are still more male than female speakers. Speakers of other genders figure in the dataset as well, but in negligeable numbers compared to the leading categories.

Some statistics on the quotes:

Not all speakers are quoted the same amount. Let's look at the distribution of quotes per speaker:

As we can see above, it's clear not all the speakers have the same representation in the media, and thus our dataset. Although most speakers have less than 1000 quotes in the data set, some are quoted disproportionately. Let's now take a look at the number of quotes by speakers of each gender:

We can see a significant change in the distribution. By looking at the percentage of quotes by each gender, we notice that men represent over 70% of the quotes present in our dataset, while gender minorities representation is negligeable.. We will focus on the male and female gender from here on out.

How we rate self-confidence:

As mentioned above, we based our metric of self-confidence on a sociology study, in which participants were asked to read a set of sentences, and rate the confidence of a person who would use those phrases, on a scale from 0 to 7, which we've converted to a 0 to 1 scale, 0 being unconfident, 1 meaning the speaker sounds very confident in that quote. The table below is a subset of the findings of the study:

| Phrase | Score (past tense) | Score (present tense) |

|---|---|---|

| I'm not sure, it's kind of… | 0.411429 | 0.415714 |

| Oh, I don't know, I suppose… | 0.42 | 0.431429 |

| I suppose… | 0.477143 | 0.477143 |

| I'm guessing, but I would say… | 0.417143 | 0.484286 |

| I'm certain… | 0.842857 | 0.935714 |

| I'm positive… | 0.851429 | 0.938571 |

| I'm absolutely certain… | 0.904286 | 0.944286 |

There are different scores associated with present tense and past tense, as it has been found that it affects percieved confidence. We searched the quotes for matches to the phrases found in the article (from here on out referred to as confidence expressions) using NLTK, and assigned the score of said phrases. For quotes in which we found multiple confidence phrases, we kept the highest score. We then averaged the scores of all quotes by the same person, which gives us the estimated confidence score of a speaker.

Here is the distribution of scores of quotes:

The data set from the sociology paper did not assign scores below 0.4, so distribution ranges from 0.4 to 1.

The distribution of scores of speakers:

We can see two significant peaks, which correspond to the past and present tense scores of I think (respectively 0.58 and 0.66). We can also note that most of the scores are between 0.575 and 0.875. Note that the minimal associated score for the confidence expressions we used was 0.42, this is why we don't observe score under this value.

Analysis

Which is more confident: men or women ?

To answer this question we compared the confidence scores of women and men. Here is the distribution of scores for men and women:

Confidence scores of both genders follow a similar distribution, but the peaks at around 0.58 and 0.66 are much higher among men than women. We peformed a bilateral t-test on the score mean, which showed there was a significant difference between men and women (p-value = 0.027). Since the p-value of the unilateral t-test (0.013) is less than 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis (same mean for women and men) in favo of the alternative hypothesis: women's score mean is higher than that of men.

Given social context, we would have expected women to be less confident than men, however results seem to show the opposite! We will continue our analysis by looking into expressions most commonly used by each gender.

What expressions do the speakers use?

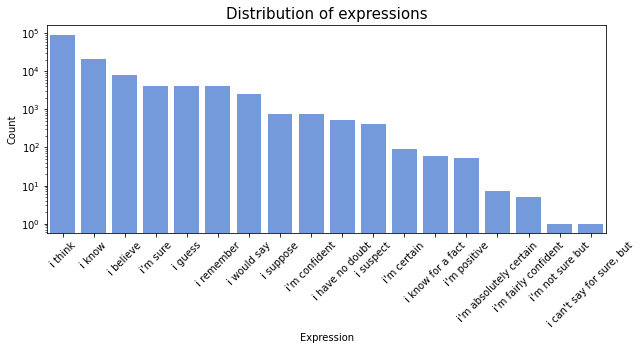

Now that we've established the scores of speakers, let's take a look at what kind of phrases hide behind the values. We first looked at the most commonly used confidence phrases by speakers:

Unsurprisingly, I think (scores for present and past tense are 0.67 and 0.58 respectively) and I know (scores for present and past tense, 0.92 0.87 respectively) take the top two spots, and are used over ten thousand times each. The values also correspond to the peaks visible in the score distribution of speakers shown previously.

Men vs. Women

Let's compare the expressions used by men and women:

We can see the top 3 expressions are the same, however after that the order changes slightly: the fourth most used expression by men is I'm sure (scores present & past: 0.86, 0.79), and the sixth one is I remember (scores present & past: 0.75, 0.74), whereas they are swapped in the women's ranking. The same can be said also for I'm confident (scores present & past: 0.92, 0.87) and I suppose(scores present & past: 0.48, 0.45), men tending to use "I'm confident" more than women.

Which expressions should you use and which should you avoid?

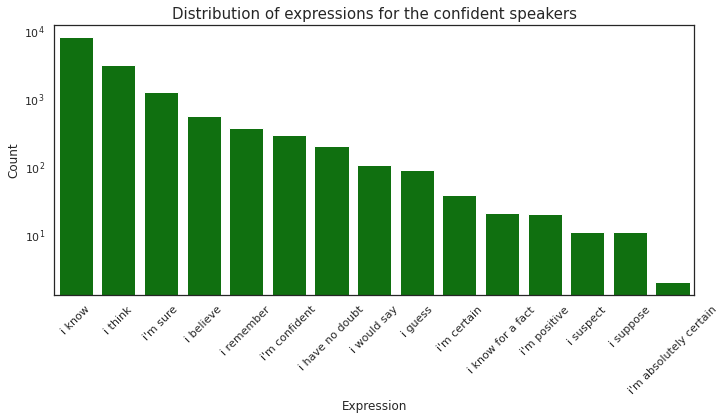

As we were able to establish a confidence score of speakers, let's take a look at the expressions used by the least and most confident speakers:

Concerning the confident speakers, we can note some changes in the order of the used confidence expressions, for example I know (0.92 for present, 0.87 for past) being more use than I think (0.67, 058). The order of most used expressions the least confident speaker is very different, confidence phrases with very high score like I know , I'm sure (0.86, 0.79), I'm confident (0.92, 0.87) are really less used. They also use more often confidence expressions with low score like I guess (0.54, 0.51) and I suppose (0.48, 0.45).

Does being a politician influence self-confidence?

Politicians, being public figures, often have to speak in front of large crowds. This should obviously better their speech skills, but would they really be percieved as more confident than other people?

To establish this, we used a subset of our data, only keeping US citizens. We then compared the scores of US Congresspeople to that of citizens.

First, the distribution of scores of people in the US congress versus not:

The distribution of scores of Congresspeople is smoother, most speakers having scores between 0.6 at 0.75, whereas the scores of normal citizens show the same peaks as prevously. Although the distribution is different, a statistic test shows there is no significant difference in score mean between the two groups (p-value = 0.75) for a 0.05 cutoff value.

Let's take a look at whether that changes if we focus on either gender:

Distributions of Congressmen and Congresswomen are also smoother than their civilian counterpart. Bilateral t-test show significant difference in neither score means (p-values = 0.13 and 0.08, for men and women respectively).

Lastly, let's see if the score distribution across genders varies among Congresspeople:

In this graph we can clearly see the distribution of Congresswomen's score seem slightly above the Congressmen's. T-test statistics (p-value = 0.0041 for one-tailed test) allow us to reject the null hypothesis (equal scores between Congressmen and Congresswomen) in favor of the alternative: Congresswomen have a higher confidence score than Congressmen.

# ConclusionHaving initially hypothesized that women would express less self-confidence than men, statistical tests showed that women’s confidence scores were significantly higher than the men’s, even though both scores follow similar distributions. This argument seems to be furthered by our comparison between US Congressmen and US Congresswomen, where again the overwhelming and significant trend was that the women outmatched their male counterparts in terms of self-confidence.

This rather unexpected result could be due to the fact that Quotebank only contained information from women out in the public eye. In order for these women to reach their current levels, they must necessarily have gone through testing times, some more trying than it might have been for men of the same status. Therefore, this group of women could already be more confident than most and thus not necessarily represent the wider female population. In contrast, perhaps the more facilitated access to power positions for the men means that the Quotebank subgroup is a more faithful representation of the general male population.